|

|

Mind, Body, Performance |

|

| |

From the International Olympic Committee's Olympic Review, XXVI-27 June-July pp. 71-74 (1999) |

| |

|

| |

Allan W. Snyder |

| |

|

| |

The Australian Olympic Committee initiated the

annual Edwin Flack lecture: an exploration of mind, body and

society, especially as it relates to sports. Edwin Flack won

two gold medals for Australia in the first of the modern Olympics,

1896. The inaugural lecture was presented at the Great Hall

of Sydney University by Allan Snyder, recipient of the 1997

International Australia Prize from the Prime Minister, and chosen

by the 1998 Bulletin/Newsweek as one of Australia's 10 most

creative minds. Professor Snyder is Director of the Centre for

the Mind at the Australian National University where he holds

the Peter Karmel Chair of Science and the Mind. He is also Professor

of Optical Physics and Vision Research and Head of the Optical

Sciences Centre.

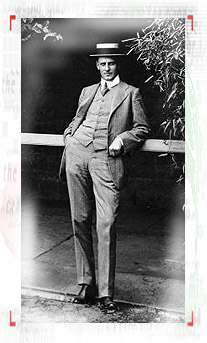

Edwin Flack was a giant! A truly great Australian.

He won two gold medals in the first of the modern Olympics in

1896. He also nearly won the marathon, but collapsed with physical

exhaustion in sight of the finish line. He gave his entire being

to win.

But, when you think about it, Edwin Flack was

a man possessed! Many might think him even mad! How else can

you explain why a person, for a mere abstraction mind you, would

actually drive themselves to physical collapse? How else can

you explain the single-minded dedication of an Olympic champion?

This is not just my assessment. Even Brooks Johnson

[Ungerleider 1995] , the great Olympic coach at Stanford University,

said:

"There is no way you can do the things necessary

to be [an Olympic champion] and not be clinically neurotic and,

in some instances, clinically psychotic ... [champions] are

very abnormal people."

Olympic athletes? Abnormal people?

But, I ask you, up front, is there really any

difference between the so-called neurosis of the athlete from

that of the artist, the scientist or for that matter any individual

who commits themselves to realise a dream? In all cases, there

is a sacrifice of the pleasures in life as normally appreciated.

What elusive spirit sustains us through the agonising

process necessary to win, necessary to realise a dream? Answer

this question and we will have unlocked one of the mysteries

of the mind, we will have discovered the element in common with

all great achievers. Answer this question and we will have captured

the crucial ingredient which lets the human spirit soar. |

| |

Edwin Flack, two-time Olympic champion (800 and 1500m) Edwin Flack, two-time Olympic champion (800 and 1500m)

in Athens in 1896.

|

Mr John Coates, Chancellor Dame Leonie Kramer,

distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen. I salute the Australian

Olympic Committee for conceiving this annual event. And it is

a singular honour for me to stand before you in this magnificent

hall, at this illustrious university, ever more illustrious

under the dynamic leadership of Professor Gavin Brown, to address

issues of fundamental importance, issues that have tantalised

and often consumed philosophers and even athletes themselves

throughout time.

Issues of fundamental importance? You might even

ask does sport belong in academia? Many intellectuals have been

dismissive of the physical. They conceptualise body and brain

as separate in both structure and function. They see the physical

as an unnecessary distraction to the mental.

Veblen [Veblen 1934] , in his influential "Theory

of the Leisure Class" saw sports as a reversion to barbarous

culture -and most assuredly detrimental to scholarly pursuit.

But compelling research strongly disputes this

claim. In particular, the American neurologist Damasio [Damasio

1994] , found that decision-making is impaired in patients who

lack awareness of their body. Damasio concluded that the mind

both learns through the body and is profoundly influenced by

the body. |

| |

In other words, we interact with the environment

as an ensemble: the interaction is neither of the body alone

nor of the brain alone. Our very reality is formed through our

interactions with this world. Our concepts and our repertoire

of mental schema are powerfully influenced by the physical.

So, the ancient Greeks actually had it right.

Plato [Douillard 1992] especially advocated physical exercise

for developing the spiritual side of life.

And the reverse is true - our spiritual side

- our mind - is critical for exquisite physical performance.

Our mindset strongly influences our performance. But, this fact

is often difficult to grasp.

So, to set the stage, I want you to imagine two

different people looking at the identical cloud formation. The

portrait painter sees a face of dignity, while the ultrasound

technician sees a diseased gall bladder. This says it all. We

view this world through our mindsets [Snyder 1996,1998]. Mindsets

that are unconscious and are shaped by our past experiences,

by our culture, our society, and even our genetic make-up. Two

athletes may enter the race with similar bodies, even similar

training, but their mindsets will be different.

|

| |

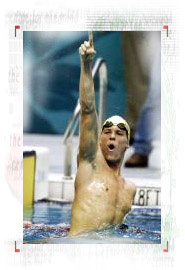

Remember Kieran Perkins at Atlanta? Remember that magical

moment when Kieran, after barely qualifying for the 1500

metre event and after being given up for lost by most

of the experts, went on a spectacular golden win for Australia.

Isn't this an example of the role of the mindset in

winning? And especially for winning in the face of adversity,

in the face of disbelievers, winning by coming from behind.

And, I assure you, sports doesn't have a monopoly on

those who come from behind to win. Just think of the many

writers, like Falkner, who persevered through years of

rejections, one book after another, before they achieved

acclaim. Or recall the myriad of artists like Van Gogh,

who painted without applause, prior to their recognition.

And, of course, there are legions of scientists whose

ground-breaking research was ignored by the establishment,

yet they continued on, they continued on to eventually

change the prevailing paradigm.

|

Kieran Perkins celebrates his victory

in the 1500m free-style event in

Atlanta 1996. Photo courtesy Aust.

Picture Library/Allsport/Al bello

|

|

| |

Now, I can just hear many of you saying: okay,

I agree, the mind might have a role, but raw talent is the crucial

ingredient necessary to fulfil dreams. You have got to have

raw talent!

How else, for example, could Susie Maroney conquer

the 200 kilometres marathon swim from Mexico to Cuba?

But, listen to this. After her swim, Maroney's

long-term coach, Dick Caine [Jeffries 1998] , said and I quote:

"Susie had no talent whatsoever".

"She's a little person who couldn't even make

a final at a state meet - coming and showing the world that

on sheer guts and determination you can do anything you want!"

And, I assure you that this sentiment is merely

an echo of views held by many others. For example, the American

Bruce Jenner [Ungerleider 1995], one of the few in the Olympic

Hall of Fame, says: "Everyone is physically talented," - winning

has to do with your mental capacity.

So, if we are to believe the experts, raw physical

talent is not always necessary to be a champion at sports.

But surely, you say, talent must be necessary

to make breakthroughs in science. Yet, that myth has been dispelled

throughout the ages [Gregory 1987] .

For example, Darwin, Einstein and Edison were

very average students whose teachers, even with hindsight, were

hard pressed to say something particularly flattering.

Obviously this is a complex subject, laden with

minefields, but it certainly would appear that 'raw talent'

as we normally define it, is not crucial for success.

So what is it that differentiates the champions

from the rest of the pack? I believe that it is primarily due

to their mindset. And here is why.

Various studies [Franken 1994, Ungerleider 1995],

show that the great achievers often create dreams or visions

of exactly what they want to do and how they are actually going

to do it. Of course, the role of dreams and mental imagery is

legendary for those in the creative arts and sciences [Gregory

1987].

But if it works in the arts and sciences, could

mental imagery possibly be of any value for enhancing an athlete's

performance? Can you, for example, imagine athletes lying about

on couches mentally rehearsing every move of their event?

Now that seems a bit crazy, just thinking about

an event, could make athletes better at it? Yet, in one recent

study [Orlick 1998] , 99% of Canadian Olympians reported that

they used mental imagery as a preparation strategy - they actually

visualised their winning performance, step by step. Some for

as many as two and three hours at a time.

And, to add to the mystery, new research from

Manchester University shows that physical strength can be enhanced

by just thinking about an exercise.

What does all this tell us? Great achievers have

a vision that they will succeed and sometimes they even see

the steps leading to their success. So, in my opinion, what

makes a champion, and I mean a champion in the broadest sense,

is a champion mindset.

A champion mindset! The world is viewed in its

totality through this mindset.

And, if you have done something great in one field,

you are far more able to do it in another. Your champion mindset

is the transferable commodity and not the skill itself.

Take Edwin Flack [Veblen], after his double gold

Olympic win in 1896, he went on to lead a firm which ultimately

became Price Waterhouse Australia and New Zealand.

Take Roger Bannister, after breaking the 4 minute

mile, went on to become a renowned clinical neurologist. And

there are champions here tonight who transferred their winning

mindset from sports to other challenging endeavours.

It is our mindsets which ultimately limit our

expectations of ourselves and which circumscribe our boundaries.

It is our mindsets which determine whether or not we have the

courage to challenge others and to expand our horizons.

The celebrated Sigmund Freud aptly captures this

sentiment when he said [Jones 1961] :

"I am not really a man of science, not an observer,

not an experimenter, and not a thinker. I am nothing but...

an adventurer.. a conquistador - with the boldness, and the

tenacity of that type of being".

In other words, from his own assessment, Freud

was not especially skilled or talented. Rather, he had the courage

to put himself into the race to begin with. He had a champion

mindset!

So, we can now see that the so-called neurosis

of the athlete to which I alluded earlier is no pathology whatsoever.

Rather, it is the athlete's inevitable single-minded dedication

to a passion. A dedication that is fuelled and sustained by

their mindset.

The great challenge for us now is to unravel

the ingredients of our mindsets, and especially to determine

how mindset is shaped by our genetic make-up, by our education,

by our culture, our society, and even by our ongoing emotional

interactions.

I believe that sports provides a unique platform

for this exploration. And, who knows, training regimes may ultimately

be tailored to each athlete's personal background.

I have been exploring what it takes to excel

at sports. But, why do we ever direct our minds to sports in

the first place? Why is sports so incredibly alluring?

It seems quite bizarre that adults bother to engage

in sports. And even more bizarre, that hundreds of millions

of people worldwide are passive spectators of sports.

For example, traffic accidents have dramatically

fallen during the televised world series . And, not only the

traffic stopped. Viagra sales have plummeted during the series

. As Rupert Murdoch , says: "Sport absolutely overpowers film

and everything else in the entertainment genre".

Obviously, for something to be so alluring, it

must be appealing to our most fundamental human make-up. And

we would expect this appeal to be manifest across cultures and

throughout time.

It has! The ancient Egyptians and the people

of Mesopotamia had a tradition in athletics at least 5,000 years

ago. Tombs that are over 4,000 years old depict sophisticated

wrestling scenes. And sport was central to the culture of ancient

Greece: the Olympic Games are themselves nearly 3000 years old.

But, I wonder how many of us believe that sport

was brought to Australia by the Europeans? |

| |

Aborigines with boomerangs, late 1800s. Aborigines with boomerangs, late 1800s.

The Boomerang

was chiefly used for

sports. photo courtesy AIATSIS.

|

For those who do, just listen to this European

account of first contact. It describes the Victorian Aboriginal

game of ball; a game which you might well consider to be a progenitor

of Australian Rules [Smith 1878].

"The men and boys joyfully assemble when the

game is to be played. They make a ball of possum skin - somewhat

elastic but firm ... It is given to the foremost player who

is chosen to commence the game. He does not throw it [as Europeans

do], but drops it and at the same time kicks it with his foot,

using the instep for that purpose. [The ball is propelled] high

into the air, and there is a rush to secure it - such a rush

as is commonly seen at football matches amongst our own people.

Some will leap as high as 5 feet or more to catch the ball.

The person who secures the ball kicks it again and again the

scramble ensues. This continues for hours." |

|

| |

Many other reports [Smith 1878, Roth 1987, Roth

1902] show that pre-contact Aborigines had an enormously rich

range of sports, employing balls, sticks and ingenious technical

innovations like the boomerang which, by the way, was principally

used for sports.

Of course, contemporary Australians have continued

this tradition of innovation by bringing the free style and

butterfly stroke to swimming; the crouched start to track; and

many others.

Finally, I want to emphasise that pre-contact

Aborigines demonstrated the qualities upon which the Olympic

movement itself was founded - fair play, competitiveness and

delight in one's performance.

These and many other observations about pre-contact,

non-industrial societies underscore the fundamental nature of

sports to our very human fabric.

Over the millennia, sports have been transmogrified

from a localised small scale activity like that of the pre-contact

Aborigines, on through to the Olympic Games of ancient Greece,

and then on to the truly global arena which it occupies today.

So what next?

Where is our vision of the future? What is the

challenge for the new millennium? We are, after all, limited

only by our mindsets.

Isn't the Olympic movement, with its global allure

and its dignity, the quintessential venue for the exploration

of human achievement? Human achievement - across the board,

across the spectrum.

Isn't the Olympic movement the ideal platform

for encouraging the cross fertilisation of ideas about performance

from every persuasion? Isn't the Olympic Movement ready to embrace

a larger vision of itself: one more passionate about performance

in its broadest sense?

And isn't Australia the ideal country to propose

a new dimension for the Olympic Movement? After all, we are

the great sporting nation, we are a great nation of innovators,

and in Sydney 2000 we herald the Olympics into the new millennium.

Ladies and gentlemen, imagine if we could focus

the momentum and the spirit of the Olympic movement into enriching

and expanding human performance panoramically?

Imagine an interactive, worldwide Olympic forum

on the study of performance.

Make this a reality and the human spirit will

soar ever more intensely, across this entire planet.

Make this a reality and the spirit of Olympism

will breathe through us all. |

| |

Acknowledgments:

I am indebted to many individuals for their insight

and suggestions in the preparation of this lecture, especially

Jeff Bond of the Australian Institute of Sport, Michael Djordjevic

of the Australian National University, Kit Laughlin, physical

educationalist,

Herb Elliott of the Australian Olympic Committee,

Nick Green of the Gold Medal winning "Oarsome Foursome", Chris

Horsley of PA consulting, Kirsty Galloway McLean of the Centre

for the Mind, Nicolas Peterson of the Australian National University

and Mandy Thomas of the University of Western Sydney.

Related references:

D. Calhoun, Sport, Culture and Personality, 2nd ed, Human

Kinetics Pub, Illinois (1987)

M. Csikszentmihalyi, 'A response to the Kimiecik

& Stein and Jackson papers', Journal of Applied Sport Psychology,

(4), 181-183 (1992).

Pierre de Coubertin, Olympic memoirs, International

Olympic Committee, Lausanne (1997).

A.R. Damasio, Descartes' error - emotion, reason

and the human brain, Picador, London (1994).

R.M.W. Dixon, W.S. Ramson & M. Thomas, Aboriginal

Words in English: Their Origin and Meaning, Oxford University

Press, Melbourne (1990).

J. Douillard, Body, mind and sport - the mind-body

guide to lifelong fitness and your personal best, Crown Trade

Paperbacks, New York (1992).

M. Dyreson, Making the American team, University

of Illinois Press, Chicago (1998).

R.E. Franken, Human motivation, Brooks Cole,

Pacific Grove (1994).

O. Grupe, 'Sport and culture - the culture of

sport', International Journal of Physical Education, (31), 15-26

(1994).

C. Hannaford, Smart moves - why learning is not

all in your head, Great Ocean Publishers, Arlington (1995).

J. Hargreaves (ed.), Sport, culture and ideology,

Routledge & Kegan Paul, London (1982).

P. Jackson and H. Delehanty, Sacred hoops, Hyperion,

New York (1995).

S.A. Jackson, 'Athletes in flow: a qualitative

investigation of flow states in elite figure skaters', Journal

of Applied Sport Psychology, (4), 161-180 (1992).

G. Jarvie (ed.), Sport, racism and ethnicity,

Falmer Press, London (1991).

N. Jeffries, 'The craziness that lets our marathoners

go the distance', The Australian, 3 June 1998.

M. Johnson, The body in the mind: the bodily

basis of meaning, imagination, and reason, University of Chicago

Press, (1987).

E. Jones, The life and work of Sigmund Freud,

ed. L. Trilling and S. Marcus, London Hogarth (1961).

D. Kellner, 'Sports, media culture, and race

- some reflections on Michael Jordan', Sociology of Sports Journal,

(13), 458-467 (1996).

J.C. Kimiecik and G.L. Stein, 'Examining flow

experiences in sport contexts: conceptual issues and methodological

concerns', Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, (4), 144-160

(1992).

K. Kreiner-Phillips and T. Orlick, 'Winning after

winning: the psychology of ongoing excellence', The Sport Psychologist,

(7), 31-48 (1993).

J.W. Loy, Jr and G.S. Kenyon (eds), Sport, Culture

and Society, Collier-Macmillan, London (1971).

N. McCaffrey and T. Orlick, 'Mental factors related

to excellence among top professional golfers', International

Journal of Sport Psychology, (20), 256-278 (1989).

J. MacClancy (ed.), Sport, identity and ethnicity,

Berg, London (1996).

R. Mandell, Sport: a cultural history, Columbia

University Press, New York (1984)

J.A. Mangan and R.B. Small (ed.), 'Sport, culture

, society - international historical and sociological perspectives',

Proceedings of the VIII Commonwealth and International Conference

on Sport, Physical Education, Dance, Recreation and Health,

Conference 1986 Glasgow 18-23 July, London (1986).

W.P. Morgan (ed.), Contemporary readings in sport

psychology, Thomas Books, Illinois (1970).

H.S. Ndee, 'Sport, culture and society from an

African perspective: a study in historical revisionism', The

International Journal of the History of Sport, (13), 192-202

(1996).

T. Orlick and J. Partington, 'Mental links to

excellence', The Sport Psychologist, (2), 105-130 (1988).

W.E. Roth, Ethnological Studies, North-West-Centre

Queensland Aborigines, Edmund Gregory, Government Printer, London

(1897).

W.E. Roth, 'Games, sports and amusements', North

Queensland Ethnography, Bulletin No. 4, Brisbane (March 1902).

J.A. Samaranch, 'Sport, culture and the arts',

Opening Ceremony, Games of the XXIV Olympiad in Seoul (1989).

R.J. Samuelson, 'The American sports mania',

Newsweek, September 4, 1989, p. 49.

R.B. Smith, Aborigines of Victoria, John Fevres,

Government Printing, London (1878).

A. W. Snyder, 'Shedding Light on Creativity',

Australian and New Zealand Journal of Medicine (26), 709�711 (1996)

A.W. Snyder, 'Breaking mindset', Mind and Language,

(13), 1-10 (1998).

S. Ungerleider, Quest for success, WRS Publishing,

Waco (1995).

T. Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class, The

Modern Library, New York (1934)

C.G. Vogler and S.E. Schwartz, The sociology

of sport - an introduction, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs

(1993).

L.R.T. Williams, M.H. Anshel and J-J Quek, 'Cognitive

style in adolescent competitive athletes as a function of culture

and gender', Journal of Sport Behaviour, (20) 232-245 (1987).

|

| |

|

|